- Home

- Courses

- Cinema Exhibition Training

- Training for Non-Technical Cinema Employees

Curriculum

- 7 Sections

- 47 Lessons

- Lifetime

- Artistic Intent – Why We Are HereThe Producers and Directors all believe that if they make their vision come to life – make their story into a movie – it will be shown in a way that allows the audience see and hear what they created with the same splendor they realized. Were they wrong?2

- Quality Management BasicsIf something is managed properly, then there is control over the quality of the items being delivered, and assurance that the end user will be satisfied. Quality Management | Quality Control | Quality Assurance12

- 2.1Ideas Behind The Checklist

- 2.2Security and You

- 2.3Training and You – and the ISO 9001 Management System – Part 1

- 2.4Routines to Self-Certify – Checklists and Employee Training – Part I

- 2.5Routines to Self-Certify – Checklists and Employee Training – Part II

- 2.6How to: Manager’s Walk Through

- 2.7How to: Manager’s Walk Through – Part 2

- 2.8Units of Measurement25 Minutes

- 2.9Where to Judge The Auditorium

- 2.10Forensics, Encryption, KDM, CMS, FLM and 3 Letter Acronyms

- 2.11Alternative Content = Non-Cinema Tech

- 2.12Units of Measurement – Part 2

- Cinema Basics – AudioSome say that a movies sound is 50% of the movie. So, it better be good, eh?7

- Cinema Basics – PictureSound has nuance. Picture has a thousand words for nuance. Let's learn some.7

- Making MeasurementsYour picture and sound equipment get calibrated according to a schedule that management thinks is appropriate for your facility – sometimes in 6 month or 12 month or 18 month intervals. But we all know that things happen in between. With the right tools, you can become the judge.4

- Accessibility EquipmentSome of our customers use the large speaker systems to know what the actors are saying, some read the words with special "closed caption" equipment...some listen to special tracks on headphones. The equipment is called Accessibility Equipment. We have to understand it and test it to make certain our customer gets the best experience possible.14

- 6.1The Other-Abled, and You

- 6.2Accessibility To Inclusion In Cinema – Prelude

- 6.3Promise, Promises and Great Expectations

- 6.4The Access Community

- 6.5Accommodation, In General

- 6.6Accommodation, Open Captions

- 6.7Accommodation, Closed Captions

- 6.8No Technology Before Its Time

- 6.9Industry Coordination

- 6.10Different Paths; …and Finally, Results

- 6.11DCP Production – Narration and Closed Caption Creation

- 6.12Currently Available – “Personal” Closed Caption Solutions

- 6.13Specialized Audio Systems for the Blind and Partially Sighted

- 6.14Signing In Cinema

- EmergenciesLife happens in real time. Sometimes we read about it. More rarely, we are there. And after, we wish that we could have practiced a little bit before being thrown into it.1

Units of Measurement

Basic Need for Terms

This lesson about measurements might get a little technical, but we will try to keep it light.

Remember that saying from the baseball player Yogi Berra? He said,

“In theory, there is no difference between theory and practice.

In practice, there is.”

We find that is true all the time. In theory, 10 minutes exists. We say, “10 minutes and I’ll be done with this!” We say, “Give me 10 minutes, then we will go.” In practice, it is always 12 or 15 or more minutes. 10 minutes doesn’t really exist.

In theory, we don’t really need to know each little term involved in the measurement of sound and light. We also don’t need to know why engineers and technical people expect (and respect) the terms.

In practice, if a word or concept seems important but we can’t grasp it, just learning these little things will take us out of that sleepy “swimming in mystery” feeling.

So, let’s do some grasping – just enough so that we get enough information without diving into the confusions of the internet. Make drawings, use paper clips and anything on the desk to represent the words and concepts and don’t be afraid to write us a note to tell us what is still confusing or too high of a jump. Thanks!

The Standards List

There is a group called the International Organization for Standardization. Most people call this the ISO. As you can guess, the ISO organizes standards. Other groups bring standards to the ISO, for example standards about fire safety or electrical safety. For our industry, the Society of Motion Pictures and Television Engineers (SMPTE) develop standards and brings them to the ISO for worldwide implementation.

The ISO also organizes the most basic of definitions. The experts have decided that there are 7 basic units of measure. Everything else can be derived from these. These International Standard Units are abbreviated as SI Units. They are:

| Symbol | Name | Quantity |

| s | second | time – a defined part of a minute, a part of an hour, a day, etc. |

| m | meter | length – a measurement based upon the speed of light |

| kg | kilogram | mass – a property measured by resistance to motion, but also sometimes just the weight of things |

| A | ampere | electric current– named after the French scientist who developed the link of electricity and magnetism |

| K | kelvin | temperature – named after an Irish scientist, and defining 0 degrees as when all motion stops |

| mol | mole | amount of substance – based on the ‘molecule’, which is a combination of atoms |

| cd | candela | luminous intensity – originally based on the amount of light from a particular type of candle |

You don’t need to know much more than these basic ideas about most of these terms.

For example: You can go your entire life without using the mole unit – even if it is fun to think that there is a single number that scientists use for counting the number of atoms in a box. But, we don’t have that box and we don’t deal with molecules or atoms. We deal with light and sound.

For example: In the same way, only people in a special part of the science world use the Kelvin scale. We care about the temperature in the auditorium, but we don’t care about absolute zero like science people do.

We Do Use Seconds, and Distance

Most people will also know what a second is, and we should all be glad that a second is accurately defined and everyone uses the same definition around the world.

In the cinema auditorium we will use the second since sound travels so many ‘lengths’ of distance every second.

That length is usually called a meter, and sometimes spelled: metre. Some countries – well, one country – uses the length of feet. A foot which is about 1 third of a meter (or one meter is a little more than 3 feet). Put your fingertips together under your chin. The distance from elbow to elbow is just about 1 meter. Try this out.

Sound travels at 383 meters per second. For the Americans, that is over 1,000 feet in one second. That is pretty fast. Most auditoriums are not that long. Imagine 16 tennis courts end to end. Someone smashes the ball. A person at the other end hears it a second later.

What does that tell us? It tells us that the sound from the front speakers gets to the audience in less than a second. How much less? That depends on the length of the auditorium, right?

But the speed of sound is nothing compared to the speed of light. Light goes almost 300,000,000 meters per second – 3 hundred million meters every second! For our purposes, that is instant.

Amp It UP!

We usually think of “Amp” as the big heavy amplifiers in the racks on the sound side of the projector. Which is correct – “Amp” is an abbreviation for amplifier. But that is a slightly different use for the same word we have above. An amplifier increases something – for example, it amplifies sound. What it is really doing is amplifying power. And that is what “Ampere” is concerned with in the definition above.

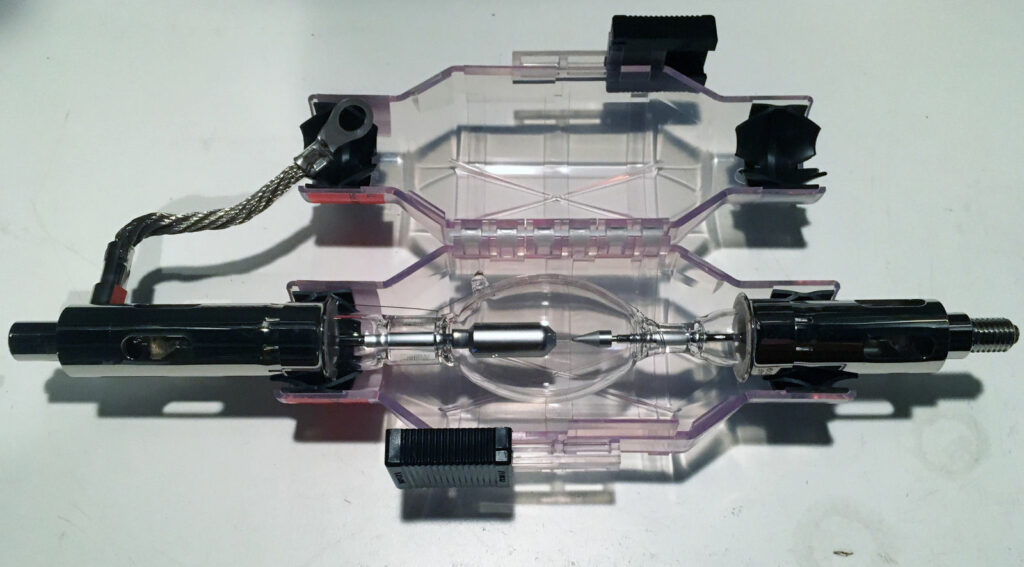

Ampere – is something that is used every day in the cinema projector. But we usually call it ‘amps’. The projector bulb uses energy to create light. That energy flows through the cables from the wall and into the lamp. That flow of energy is called a current, just like a river current. And that flow is adjustable.

Somehow – by magic possibly – the gas inside the lamp gets charged up enough to emit light. Not just any light, but the frequencies of light that can then be used to light up some magic mirror chips that bounce the colors that show up on the screen.

You will learn more about frequencies in the lesson called: Audio (Sound Basics): Part 2.

You will learn more about these magic mirror chips in A Look At Light – Part 1.

There are several reasons that these bulbs become less efficient at converting electricity into light.

There are two parts inside the bulb, that are separated by a gap. The electricity jumps from one to the other, which makes a continuous spark of light. Usually it is the pointy ends of the sparking parts that get corroded. In this case, corroded means that they eat themselves up. The pointy tips get pits and the pits make the sparks go in different directions instead of strait to the other pointy part. That means they need to consume more energy to make up for the electricity that goes sideways instead of straight.

We measure the the flow of that energy used to maintain a consistent spark as so many ‘amps‘. When the bulbs brightness gets weaker as it ages, we have to increase the amperage, or amps.

Sometimes people use the flow of water as a way to show the similarities of electric flow. We can do that another time, because it involves a lot more words that we do not need to learn right now. But, in the water example, if you keep the size of the hose the same but increase the amount of water going through, you are increasing the flow, and that is “amps”. What kind of water and how big a bottle – I like the bubbling water.

Weighty Subjects

There are two more Standard Units that we are more familiar with, even if we don’t use the words all the time; kilograms and candela. We use kilograms every day, because it is the unit of measure for weight. Even in the United States where pounds and ounces are still used, everything from breakfast cereal to computers and TVs also have to print the weight in kilograms or grams on the box since they also sell to Canada or other countries using grams and kilograms. Of course, speakers have weight and movie screens have weight, so we have floors that are designed to hold these weights safely. Since these things were decided years ago, and don’t change, we don’t have to think about it much.

Light Is Sensational

Candela is really the most interesting measurement for us. In the Standards List above it is called ‘Luminous Intensity’.

We are going to study this in more detail for 2 reasons. One reason is that the light is the basic thing that people come to the movie theater for. The second reason is that it if we are going to communicate to the tech what the problem is (or isn’t), then there should be no confusion about any of these details. Fortunately, there is a logic (somewhere!!??!!), and eventually we can understand each detail.

‘Luminous’ is a marvelous word that comes from the Latin word for Light, which is lumens.

Candela comes from the Latin word for ‘candle’, which creates light.

In the world of standards they don’t just use any candle. The ISO specify the particular composition of the candle so that anyone, anywhere can create the exact same light – if you happen to have a wick made out of pure platinum and a certain amount of an exact type wax.

‘Intensity’ is also an interesting word. It hides a sophistication that we need in our work.

The word Intensity is used to describe the strength of something, but it is best when we also use it with “per unit” of something. For example, speed intensity might be described as Kilometers – Hey officer, I was only going 60! – but it is best when we describe it as Kilometers per Hour – Actually, you were going 65 kilometers per hour!

In our case, Candelas deal with the strength of the light we are using. The ‘per’ that we will use is a small part of the screen size. In the old days, they used ‘square feet’. They measured the amount of light that fell on a 1 foot x 1 foot square of the screen. Now, we use meters, so we say Candelas per square meter.

The abbreviation of Candelas is ‘cd’. The abbreviation for ‘per’ is the slash sign: ‘/’. The abbreviation for square meters is an ‘m’ with a little 2 placed behind and above it. So, for 10 candela per square meter we write: 10 cd/m2.

Actually, the standard for a cinema is to be able to put 48 cd/m2on the screen. That is actually pretty bright. If you had to look at it quickly onscreen you would probably blink your eyes for a second, or turn your head away. But, outside on a sunny day, the reflections of the sun on the cars will be 10s of thousands of cd/m2.

Luminance Gets In Your Eyes

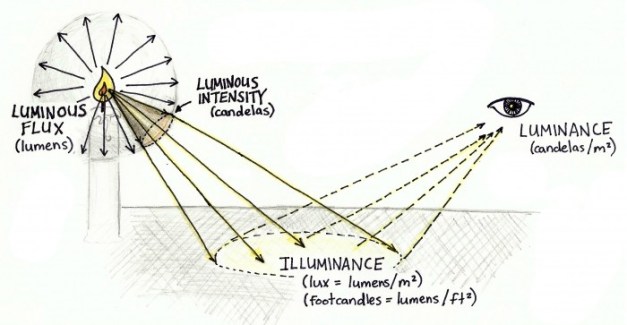

To understand the sophistication of this better, let’s look at this picture.

To understand this better, let’s look at this picture.

First, we see that the energy from the burning wick is leaving the candle in all directions. Instead of energy coming from a wall plug, the energy is coming from the wax of the candle. The energy of the wax is being converted by the fire, and emitted into the air as heat and light.

Can we ignore the word ‘Flux’? No? OK. Let’s just say that comes from the Latin word for ‘flow’, with an example of a river flowing, or air flowing. Yes – just like the ampere being the flow of the electricity~! Nice one! In this case, light is flowing, or a science person will say, lumens are flowing. But what is the intensity?

Some of the light hits the ground with enough intensity to see or measure. Notice that, even though the ground is bright, the ground is not creating light. It is receiving light, and if someone wants to measure how much light it is receiving, we call that light ‘illuminance’. Professional photographers do this all the time. They put a meter next to a persons skin and measure Lux. Of course, they are also interested in the light coming into the camera. But before that, when they are measuring the light on the scene, they measure the effect of their lights and reflectors hitting the walls or people in “lux”. Lux is an abbreviation for lumens per square meter. Yes, we learned ‘meters’ just above.

Lux and Illuminance is not something that we deal with in the cinema. We deal with ‘Luminance’. Luminance is the light being emitted from something that is being received by the eyes (or the camera).

In this modern age, this has two uses. One is the light being reflected from the screen. The other is the light coming from the giant LED walls that some cinema theaters are putting in. That light – the amount of light getting to the eyes of the audience – is the interesting measurement of light for us. Luminance. Candelas per square meter.

Summing Up with a Few Nits

So now, after many definitions, we can sum this up.

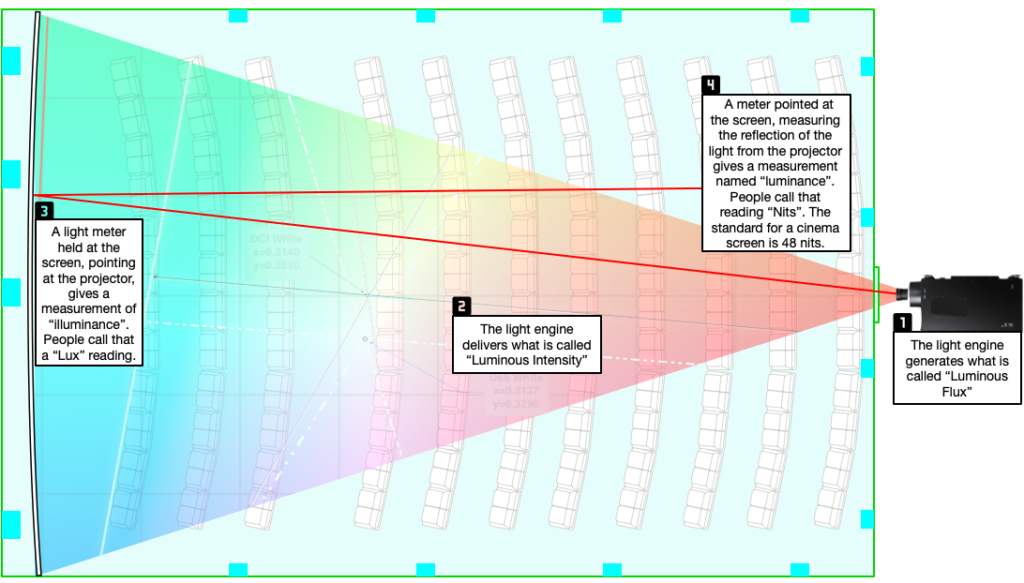

In the cinema, first we have the energy from the projector. That energy leaves the projector as light. Differently from the candle’s light, the projector’s light flows from the lens in only one direction. Because it is flowing from the source, the projector’s light is called – everybody say it together now – Luminous Flux.

The amount of the projector’s light is called – Luminous Intensity. When intensity was coming from the wall plug, we said that we measured amps. Sometimes you will see this measurement called Watts. Watts is not really a measurement of light output – it can be used, but it will lead to confusion. It is named after James Watt, a person who studied the power of steam in the 1760s! …no association with light. So, don’t let people confuse you. Watts is power. Bulbs have an input power rating, in Watts. But we don’t change bulbs, we look at light as it leaves the projector, as it appears on the screen. Watts is a subject for another situation.

Luminous Intensity is measured in – everybody, all together – candela per square meter. All the hip cinematographers will never use that many words. They will simply say: ‘nits‘.

If we stand at the screen and point a meter into the projector lens, we are measuring – everybody? – Illuminance. Illuminance is Lux. We don’t do that. It hurts the eyes!

We cinema people point our meters at the screen. We want to measure Luminance. We measure the reflected light from the screen. (Or, in a few places with LED screens, we measure the light that is exiting from that screen full of LEDs.) We measure this because we want to know how much light is going to be received by the eyes of our customers.

And that – what our customers receive – is what is important to us.

Light can be interfered with. It can get trapped in the projection room by reflecting from the port window and back onto the wall of the projection room. It can be blocked by dirt and popcorn grease on the port window. It can even be blocked by dust in the air. It can be caught in the screen – which is weird, but believe someone if they say that an old darker screen is less reflective than a new bright shiny screen. So, to know how good the light that the customers are getting is, we have to know the light measured after it bounces off the screen.

With this picture we end this lesson. It is all background for a secret mission.

You may not know it yet, but in a ‘wax-on/wax-off’ way, eventually you are going to be able to walk into a cinema auditorium and look at the screen and say, “There is something wrong with this picture. I have to tell someone. But, I want to tell them something about the problem. “The picture is dark” or “There is no contrast” or “The colors are not saturated” are a few of the things.

But the problem is: What if the director wanted the picture to be dark? …or the colors to be unsaturated?

…and what does unsaturated mean?

There is a Part II, and there are more specific lessons. Get out now before this gets too interesting to leave!!!