- Home

- Courses

- Cinema Exhibition Training

- Training for Non-Technical Cinema Employees

Curriculum

- 7 Sections

- 47 Lessons

- Lifetime

- Artistic Intent – Why We Are HereThe Producers and Directors all believe that if they make their vision come to life – make their story into a movie – it will be shown in a way that allows the audience see and hear what they created with the same splendor they realized. Were they wrong?2

- Quality Management BasicsIf something is managed properly, then there is control over the quality of the items being delivered, and assurance that the end user will be satisfied. Quality Management | Quality Control | Quality Assurance12

- 2.1Ideas Behind The Checklist

- 2.2Security and You

- 2.3Training and You – and the ISO 9001 Management System – Part 1

- 2.4Routines to Self-Certify – Checklists and Employee Training – Part I

- 2.5Routines to Self-Certify – Checklists and Employee Training – Part II

- 2.6How to: Manager’s Walk Through

- 2.7How to: Manager’s Walk Through – Part 2

- 2.8Units of Measurement25 Minutes

- 2.9Where to Judge The Auditorium

- 2.10Forensics, Encryption, KDM, CMS, FLM and 3 Letter Acronyms

- 2.11Alternative Content = Non-Cinema Tech

- 2.12Units of Measurement – Part 2

- Cinema Basics – AudioSome say that a movies sound is 50% of the movie. So, it better be good, eh?7

- Cinema Basics – PictureSound has nuance. Picture has a thousand words for nuance. Let's learn some.7

- Making MeasurementsYour picture and sound equipment get calibrated according to a schedule that management thinks is appropriate for your facility – sometimes in 6 month or 12 month or 18 month intervals. But we all know that things happen in between. With the right tools, you can become the judge.4

- Accessibility EquipmentSome of our customers use the large speaker systems to know what the actors are saying, some read the words with special "closed caption" equipment...some listen to special tracks on headphones. The equipment is called Accessibility Equipment. We have to understand it and test it to make certain our customer gets the best experience possible.14

- 6.1The Other-Abled, and You

- 6.2Accessibility To Inclusion In Cinema – Prelude

- 6.3Promise, Promises and Great Expectations

- 6.4The Access Community

- 6.5Accommodation, In General

- 6.6Accommodation, Open Captions

- 6.7Accommodation, Closed Captions

- 6.8No Technology Before Its Time

- 6.9Industry Coordination

- 6.10Different Paths; …and Finally, Results

- 6.11DCP Production – Narration and Closed Caption Creation

- 6.12Currently Available – “Personal” Closed Caption Solutions

- 6.13Specialized Audio Systems for the Blind and Partially Sighted

- 6.14Signing In Cinema

- EmergenciesLife happens in real time. Sometimes we read about it. More rarely, we are there. And after, we wish that we could have practiced a little bit before being thrown into it.1

Audio (Sound Basics): Part 1

Sound is all around us. We don’t need any particular talent to use it. Doctors tell us that we can hear sounds in the womb.

We can make sounds with a melody using our voices and we can make sounds with a beat using our hands. We can hear sounds with our ears, and we can also feel sounds when something has a lot of impact.

There are a lot of similarities between sound and pictures – artists can make music with sounds and pictures with light. And most of us who are just learning to be artists at something, well, we either don’t pay much attention to the details and do OK, or, we are learning.

And that is where we pick up the story. To be able to judge sound, to know if it is the best possible for your clients in the auditorium – or at least acceptable – is a task worthy of your interest and study.

We should remember that there are several people who have hearing issues, which means that they don’t fit into every category of hearing. We will go through these issues later(…in The Other-Abled, and You lessons), but for now we’ll just listen to a philosophy lesson

OK; Next, Good Vibrations

For a simple definition, “Sound” is what we hear. But actually every sound involves hundreds of steps. These steps begin with a motion that takes place at one point. The drummer hits the drum, and it vibrates. The bell gets hit and it vibrates. We push air up our throats and make it vibrate.

We can’t see it, but you can visualize it by thinking about it like a pebble that is thrown into a pond.

Very quickly, that one motion starts a series of motions that spread out as waves. Like the circular wave on the water, sound is a wave that spreads out from the source.

There are some differences with the water comparison though. The first is that we see the pond surface as a flat surface. Our sound wave is different – it goes out in all directions from a speaker; left, right, strait ahead, above, and wrapping all around. It is similar to the way that a light goes out from a flame – from the top and bottom and all sides at once, every angle to every corner. The second difference is that the spreading wave, that energy spreading out from the speaker, is pushing on air. Air acts differently than water. For example; because the components of water are closer together than the components of air, the speed of sound through water is much faster, about 1,450 meters per second ! The speed of sound through the air is about 340 meters per second.

But the main thing is true – a wave of sound and a wave of light all allow energy to get to our ears and eyes.

Eventually the energy of the wave reaches our ears. It then goes inside the ears and finally (through a process that is so sophisticated that it seems like it must be magic), the wave motion turns into electricity. That energy goes down some nerves. That new energy wave of electricity transmits what we heard, that original motion, to the brain for analysis.

Sometimes the word Sound and the word “Audio” seem like they mean the same thing. But they can be different. We will say that “audio” is a type of sound that is being played through some equipment. This is the sound that we hear in the movie auditorium.

Grammar in English is complicated though, so that statement is not always true. We might say that the sound of his voice onscreen was pleasant – we won’t say, the ‘audio’ of his voice. And, we won’t say that the voice of the singer on the street had amazing ‘audio’. Instead, we would say that the ‘sound’ of his or her voice was amazing.

Whether the sound is natural or reproduced, the path to our ears is complex. You don’t need to know about most of that complexity, just like we don’t need to know about most of the complexity of the sound speaker on the wall. …or, is that supposed to be “audio speaker”?

But as a professional-in-training, you should understand enough so that you aren’t fooled by something that isn’t immediately obvious. You should be able to respond correctly if an audience member says something about the sound. For example, you could ask an appropriate question that gets a good answer which will give the tech better information, so they can fix the issue more quickly.

Because that is part of your job: To tell the technician about negative changes in the sound – a rattle, a hum, no sound, distorted sound, sound that isn’t balanced (too much or too little from one side, for example)…and where…and if possible, why.

So, we’ll start slow. We’ll cover some basics. And after you hear a test DCP (See: What Does It Mean: DCP) in an auditorium a few times – or 10 or 20 times – you can review the material in this lesson (and the next) to refine your knowledge. Perhaps you will find questions while you work that were presented when you studied, but didn’t seem important before you refined your ability to notice things. When we do this, we are learning to evaluate by significance. So, get out there and find those things that are significant, and find out those things you want to know more about.

And, please ask questions. Because no one was born with this data – everyone had to learn this. Much of it is new. Much of it is very new, and almost all of it has been refined very recently as science and technology has progressed. So, good luck to you, and good luck to us all~!

2 thoughts on “Audio (Sound Basics): Part 1”

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

World “Wild” Web??? 🤷🏻♂️

Hola Jaun García,

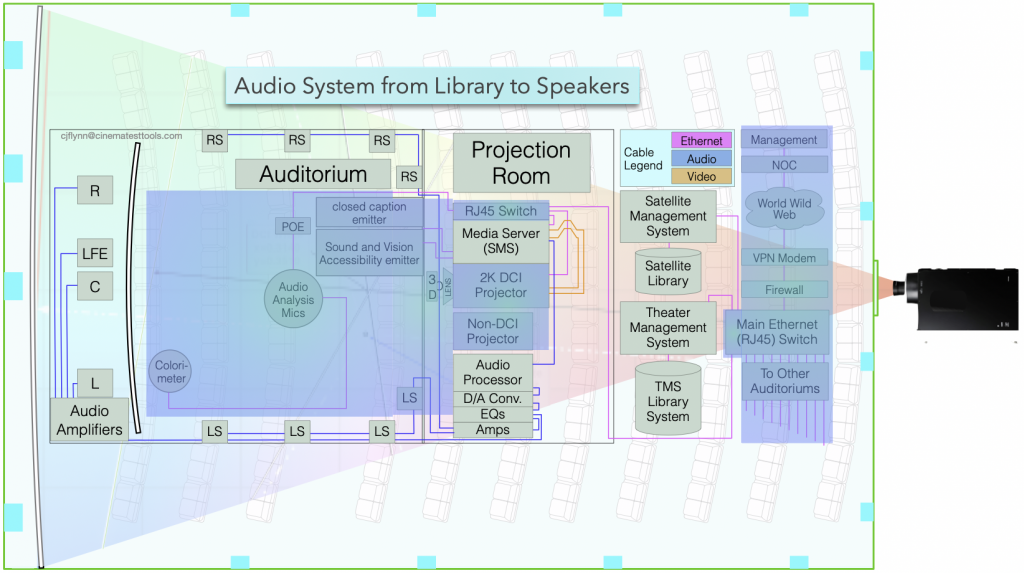

Very good eye! I made that drawing, derived from a larger one which included many cinema theaters. <https://cinematesttools.com/pdfs/DCinema_Auditoria_and_Equipment_Network_Generic.pdf> It was for a presentation many years ago and I put it in just for the joke because a serious point was made a little later.

Then I kept it for the joke when I made the smaller drawing for a presentation 2 years ago <https://www.dcinematools.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1879:loudness-in-cinema-ibc-2016-presentation&catid=114&Itemid=176>.

Does the rest of the article make sense except for this joke?